From Alleyn’s to Colliding Black Holes

Roy Williams, class of 1976It was a cold, drizzly afternoon in South London in 1973. A soccer game on the infamous “slopy pitch”. My team was playing the ball uphill. I was wondering if we could go in early if the rain started. And thinking about the Mars spacecraft that would be sending back live pictures. A wet muddy soccer ball bashed the side of my head as someone shouted PASS THE BALL!!” Such were games afternoons at Alleyn’s. But one day my friends John Bateman and Roger Shepherd showed me their “computer programme”, a few lines of FORTRAN. And then there became a new option on games afternoons: “Computing”. Volunteers were needed to carry boxes of cards to Imperial College in London and bring back the reams of paper output. Infinitely preferable to either soccer or the other option, cross-country running!

Tim Brand, John Jaworski, and David Wallace were the teachers who started up this whole idea of computers – a bizarre idea for 1973! There was a connection with Imperial College in London, a computer that would run our code, and a Card Punch installed above the wood shop. But it wasn’t just avoiding cross-country running that spoke to me. Rather, it was the thrill of coding: the machine follows its instructions perfectly and does magical things. Since then decades have unrolled, my career always propelled by the combination of computers and science, all thanks to the foresight and effort of the Alleyn’s teachers. By 1997, I was working at Caltech in California, part of the team involved in detection of gravitational waves by the LIGO project. The first detection was 2015: it was one of the signal scientific accomplishments of this century.

Astronomy has traditionally been all about light. Telescopes allowed huge steps: Galileo seeing the moons of Jupiter, Hubble understanding that our vast Milky Way galaxy is just a dot in a huge Universe. When I say light, I mean the whole spectrum of light, much of which our eyes cannot see, including radio, X-rays, and infrared, that can show us so much more than just optical wavelengths. But gravitational waves offer a new way to understand the distant Universe, a new sense in addition to our eyes and telescopes. When two black holes coalesce into a single entity, their last furious orbits generate the signals measured by LIGO. Faster and faster the orbit goes, until each collapses into the other in a great burst of energy, the combined black hole spinning and shivering. When converted to audio, the signal is a chirp, rising in frequency, sounding a bit like a bird call.

Einstein of course is the hero for everyone in LIGO. By pure thought he revolutionized physics. Suppose, he pondered, light always travels at the same speed. Suppose, he thought, gravity is not simply a force between two masses, but rather the mass bends the space, and that bending is what makes the other mass move. By following these insights, he came up with a grand theory of gravity with bizarre predictions: black holes and gravitational waves. The idea that space itself can be jiggled like jelly, and everything in that space jiggles with it.

There were two LIGO observatories built in remote parts of the USA, each an L-shape with arms 4 km long, filled with high vacuum and high-performance lasers. It was a strange place to work: people were driven by faith -- faith that eventually LIGO would detect something. By 2015, some people had been working on LIGO for 30 or even 40 years, always fearing that it might end up as a complete dud! If Nature were unkind, there might be just one stingy detection buried in noise, even after years of running, and destructive squabbling amongst the collaborators about whether to publish. But Nature was kind to LIGO, and gave us a clear signal, exactly as Einstein’s theory predicts, and has given us frequent detections since. It opened a new window on the Universe.

The event was a billion light years distant, a coalescence of two black holes yielding unimaginable power. Just as an atomic bomb energy is the result of converting the mass of a paperclip to pure energy (E=mc2) , the LIGO event converted three times the mass of the Sun to energy! Ten-to-the-33 atomic bombs! Multiple detections by LIGO are now showing the origin story of black holes, and how our own solar system is influenced and shaped by a population of black holes in the Universe, as yet hardly explored.

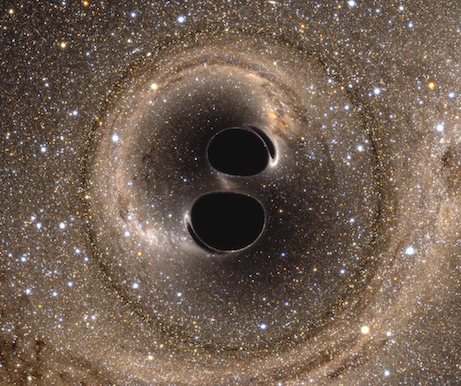

Simulation of two black holes coalescing, masses 36 and 29 solar masses. Note the "eyebrows", each

providing a view of the other black hole after light rays that started moving away from the viewpoint,

were twisted back by gravity towards the

viewpoint. See the video here.

-- courtesy SXS Collaboration

Simulation of two black holes coalescing, masses 36 and 29 solar masses. Note the "eyebrows", each

providing a view of the other black hole after light rays that started moving away from the viewpoint,

were twisted back by gravity towards the

viewpoint. See the video here.

-- courtesy SXS Collaboration